How Buffett Really Buys Stocks

Hint: It's not at 40x earnings...

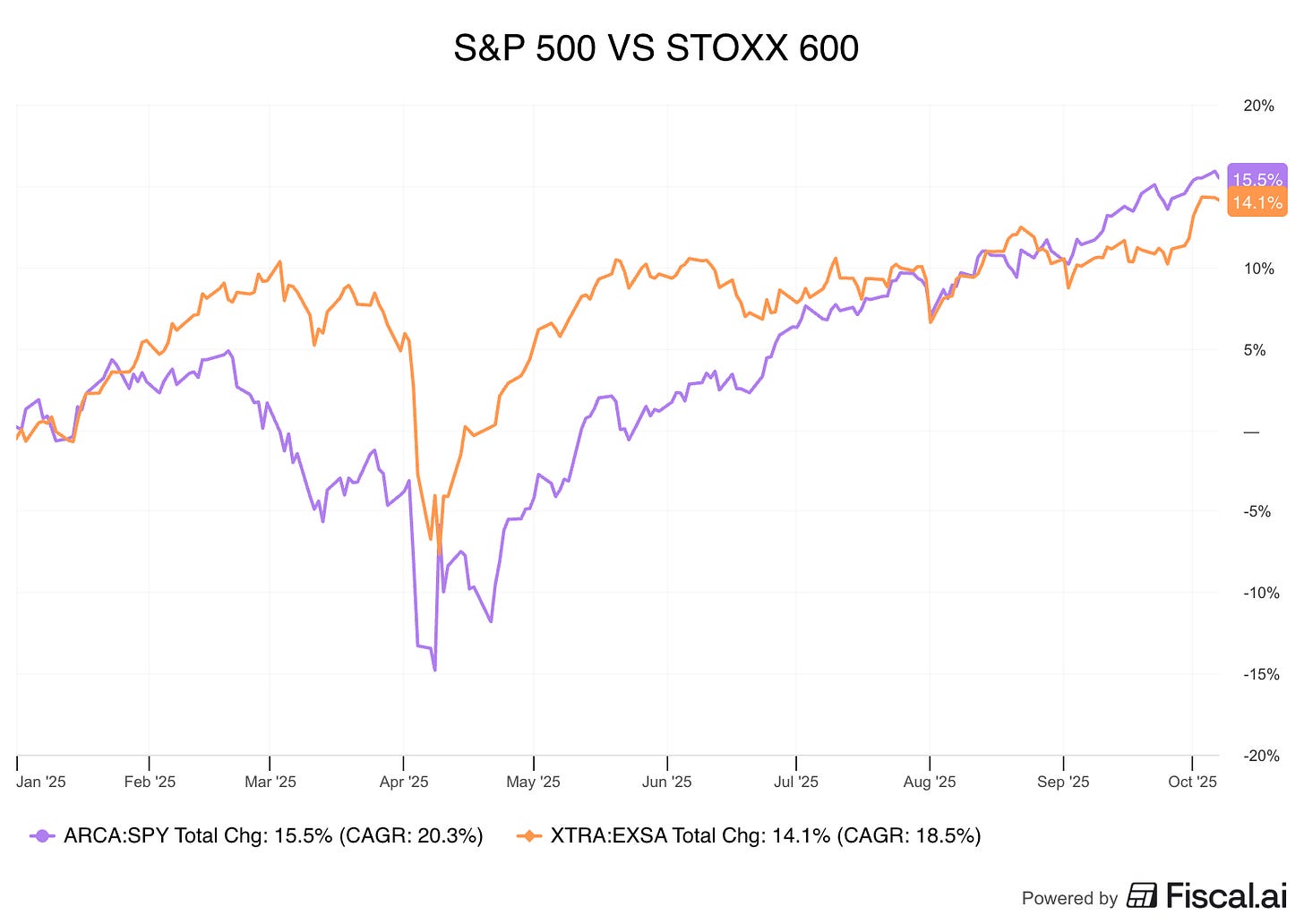

2025 has been a wild ride in the stock markets.

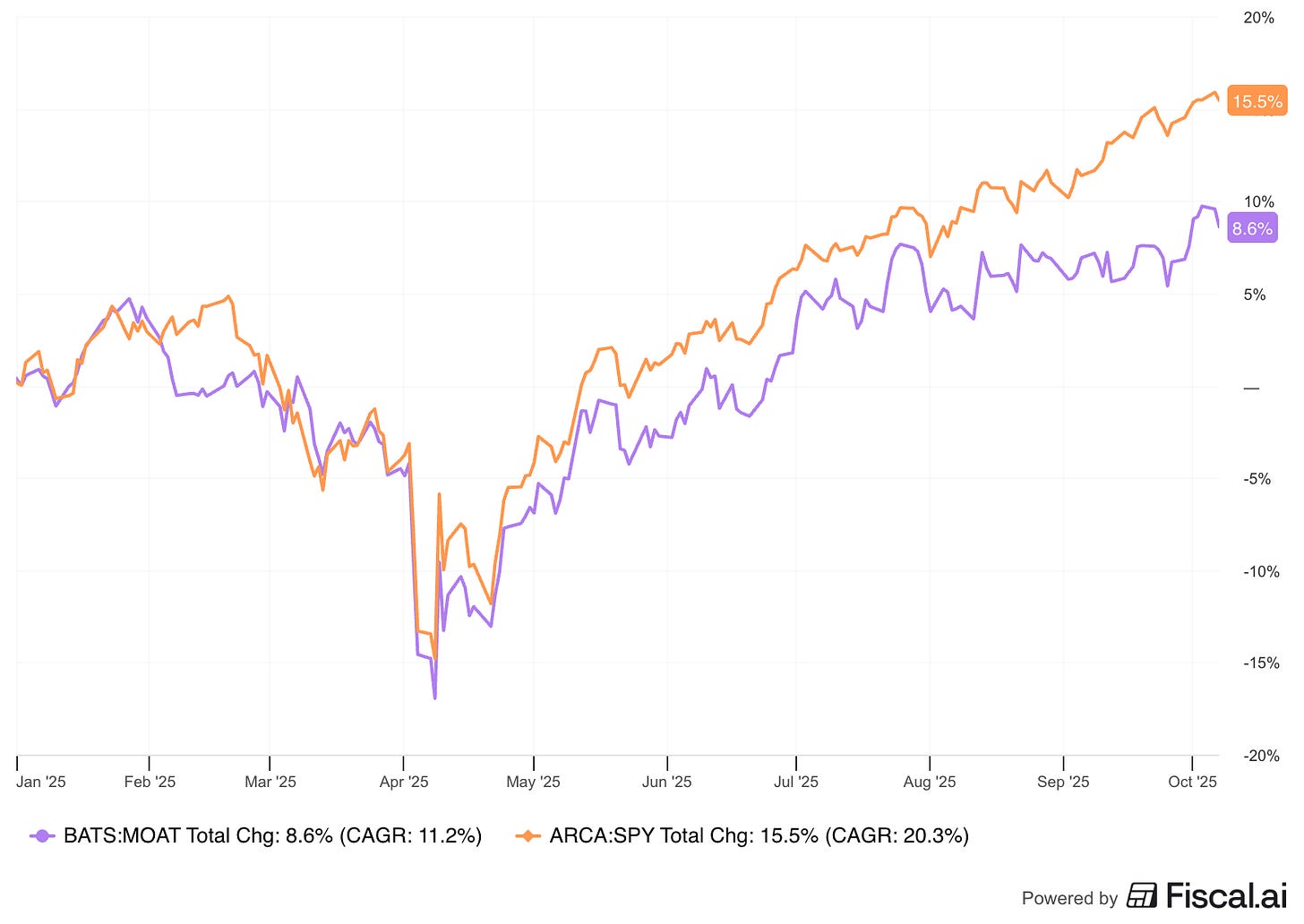

The year began with European stocks outperforming the S&P 500. America has caught up, but both indexes have done very well so far this year:

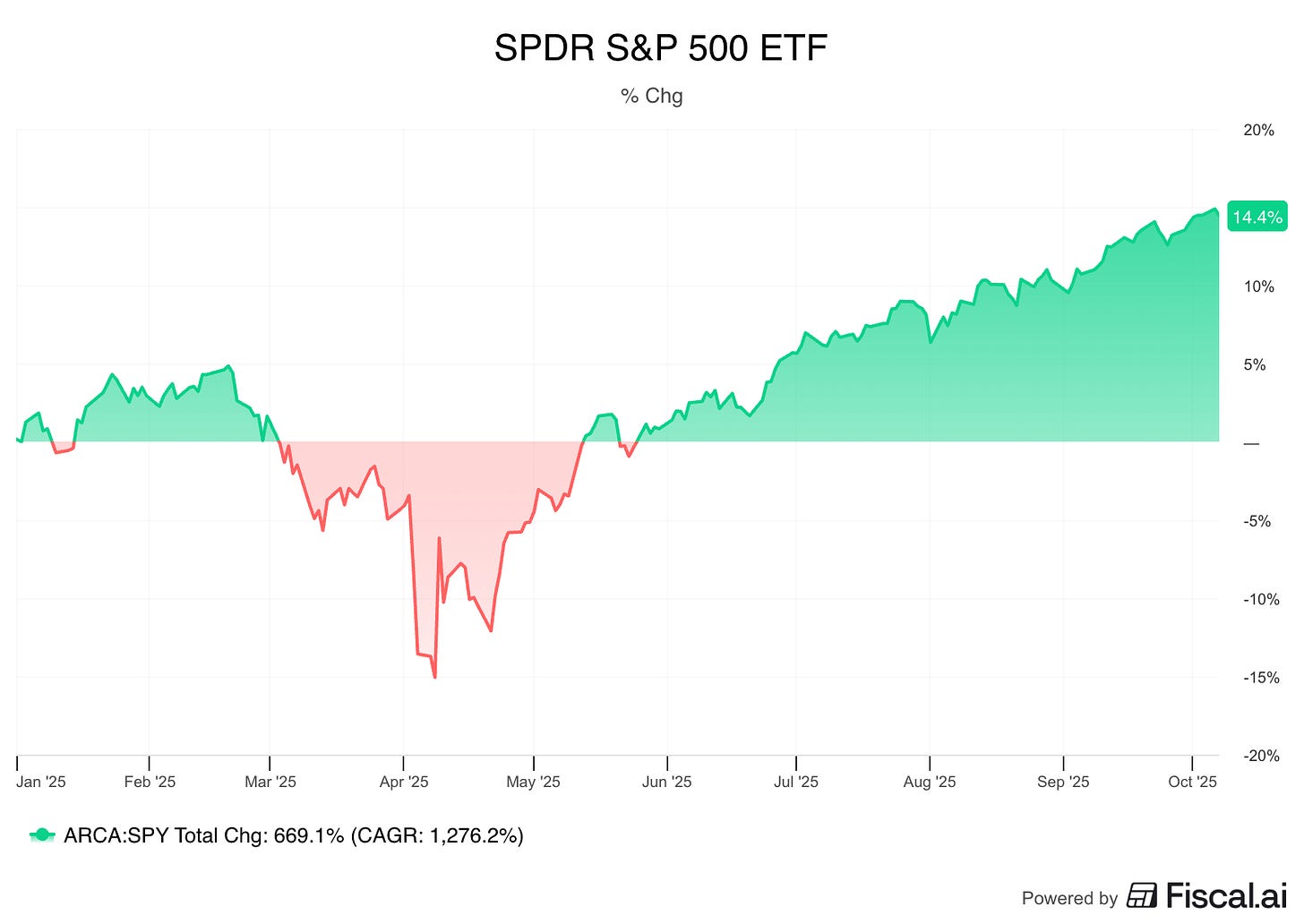

In April, the S&P 500 fell 15% after Trump announced tariffs.

Now it’s up more than 14% for the year.

That’s a great result, but investors are still unsure.

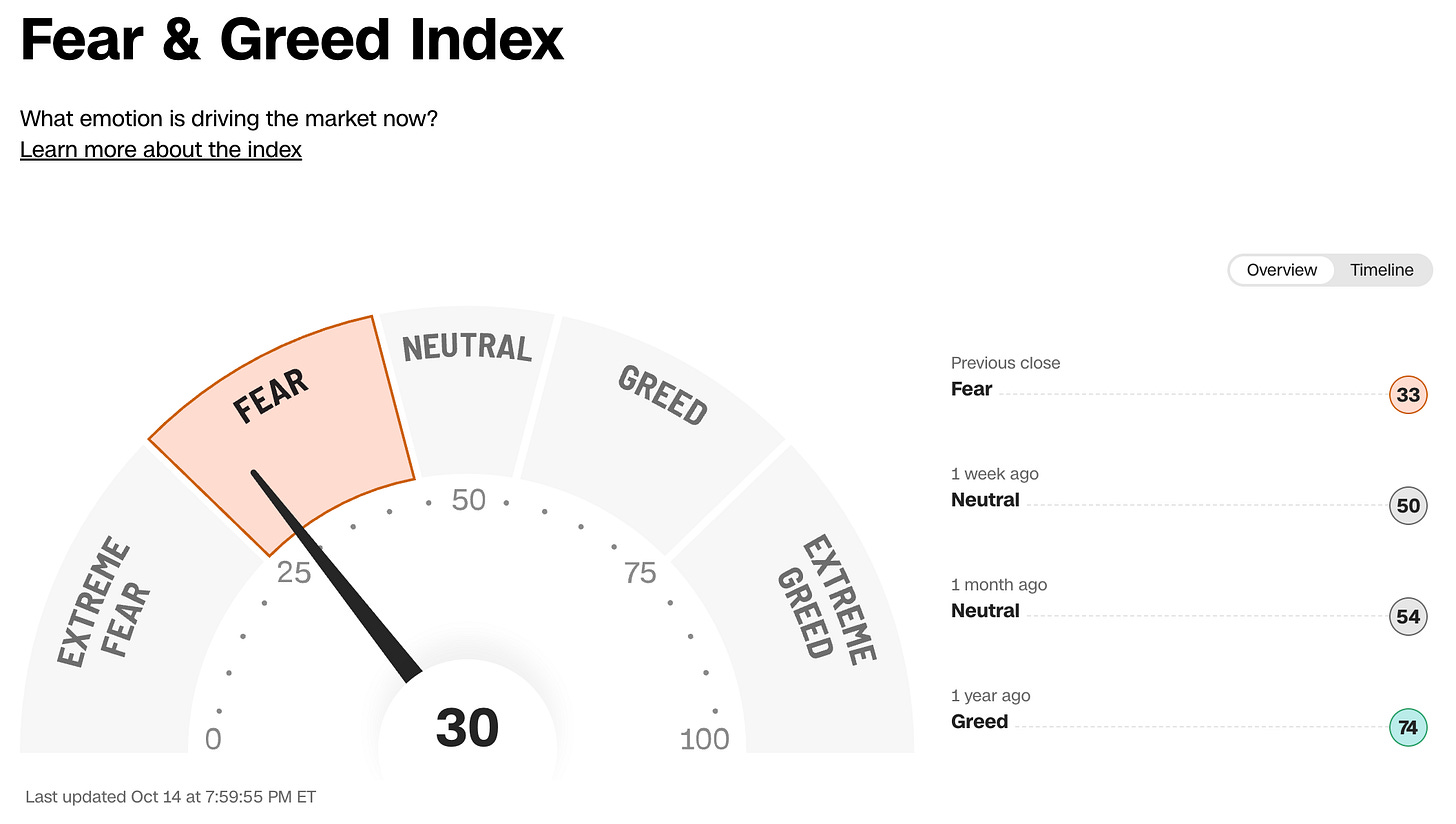

The Fear & Greed Index has moved between “Neutral” and “Fear” even with these strong gains.

We’re currently in ‘Fear’ mode.

Normally there’s a ‘flight to quality’ in uncertain times, where investors sell of risky companies and buy big stable ones. But this year, that’s not been the case.

The Morningstar Wide Moat Index has underperformed the S&P 500.

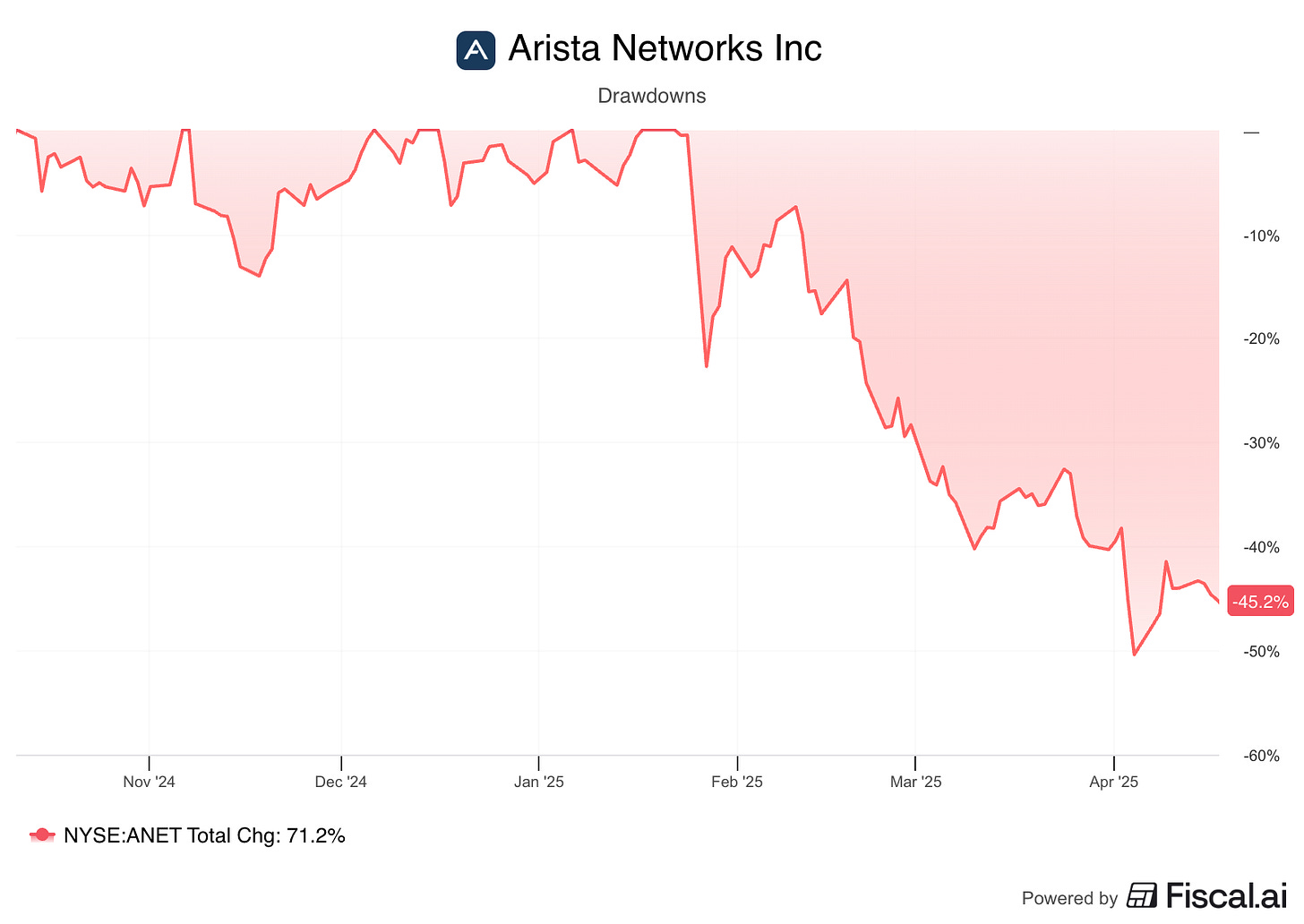

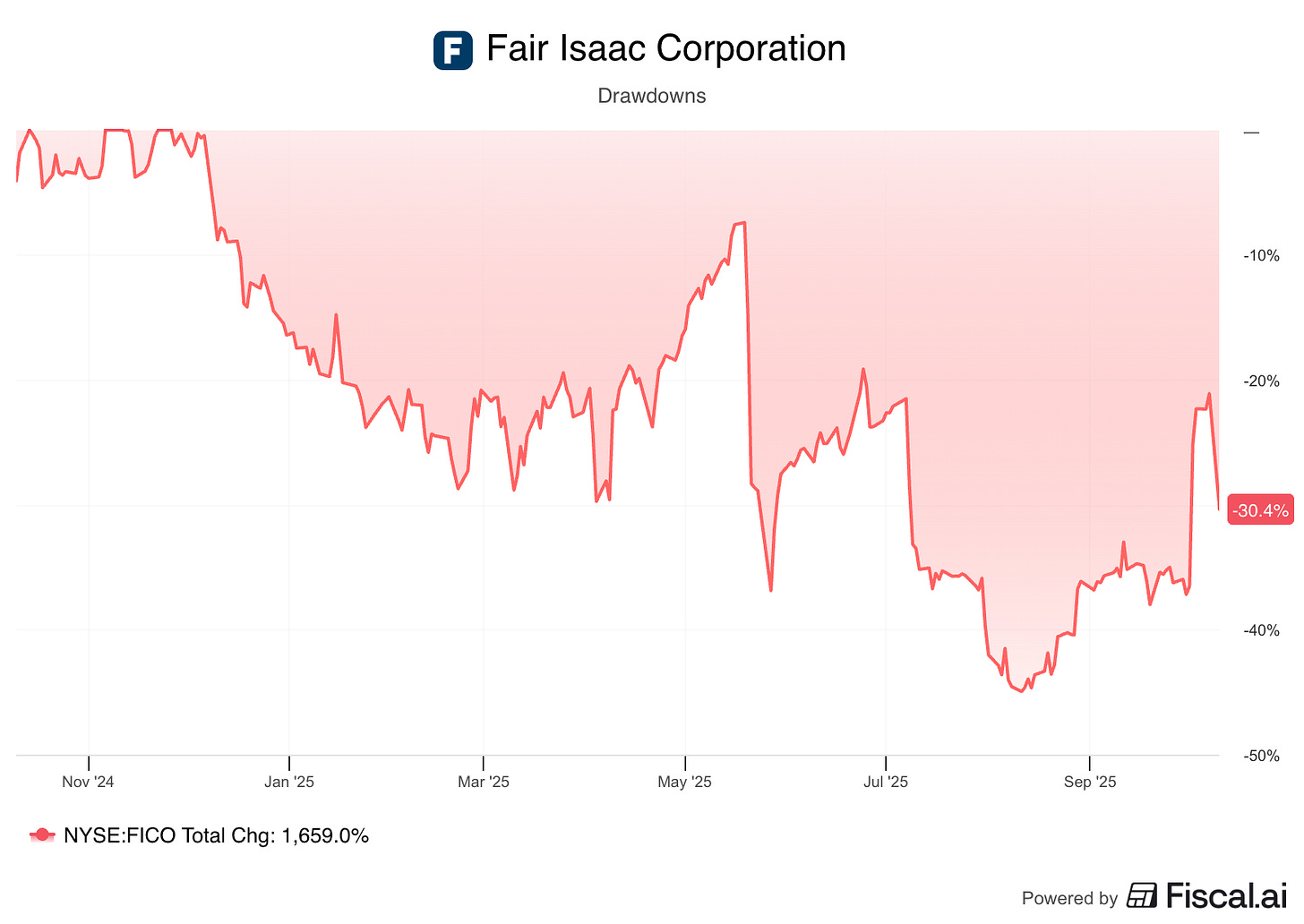

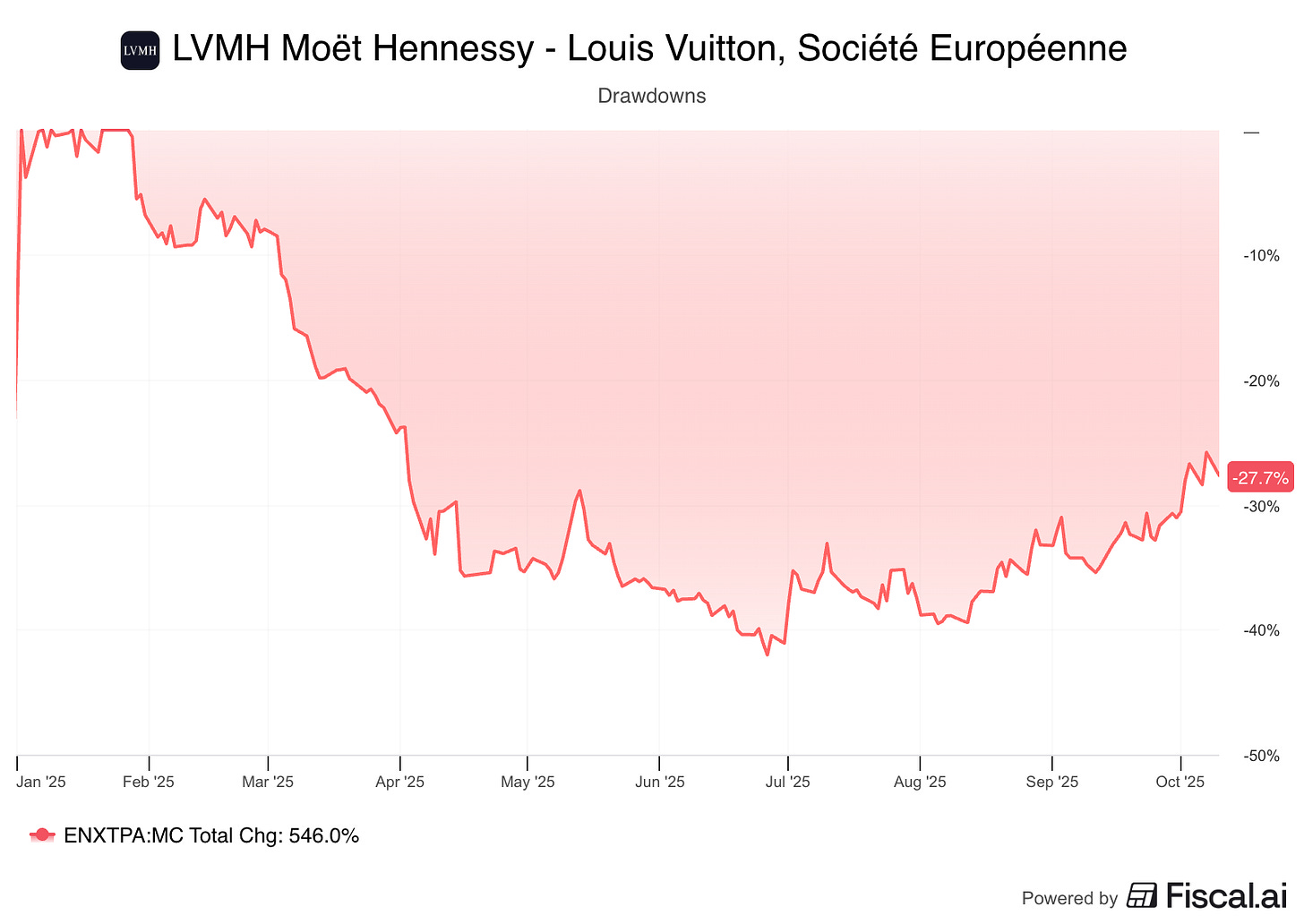

2025 has been strange in that some really well known, quality companies have had significant drawdowns.

Arista Networks (ANET) fell 45% in April, but has since recovered most of it.

Copart (CPRT) hasn’t been as lucky. It’s still down more than 30% this year.

FICO fell more than 40% in August and is still down 30% for the year.

Even Europe isn’t immune - LVMH was down 40% on the year and remains close to 30% down on the year.

What’s going on?

Valuation Matters

I think it’s pretty simple - what you pay for a business matters.

People use Warren Buffett’s transition from a ‘value’ investor to a ‘quality’ investor as justification to pay too much for good companies.

It’s true that Charlie Munger showed Buffett why it can be smart to pay more for great companies.

Buffett even called Charlie the “architect” of Berkshire in the annual letter written after Charlie died.

Everyone knows the quote, but I’ll put it in here anyway -

Couple that, with this:

‘Over the long term, it’s hard for a stock to earn a much better return that the business which underlies it earns. If the business earns six percent on capital over forty years and you hold it for that forty years, you’re not going to make much different than a six percent return – even if you originally buy it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns eighteen percent on capital over twenty or thirty years, even if you pay an expensive looking price, you’ll end up with one hell of a result.’

– Charlie Munger

So we can pay a lot for a great business, right?

Not exactly. It depends on what “a lot” means.

Price matters.

Here’s how I think about it. We can get returns on an investment from 3 places:

Earnings growth

Multiple expansion

Shareholder yield

Shareholder yield takes into account reduction in share count through buybacks, return of capital through dividends, and debt pay down.

Any increase in any of those 3 categories can make the value of a business go up.

Any reduction can make it go down.

What’s a fair price?

There are plenty of studies out there that show you can pay a higher multiple for a great business.

Surely the Oracle of Omaha has read them.

Surely he’s willing to pay up for great businesses.

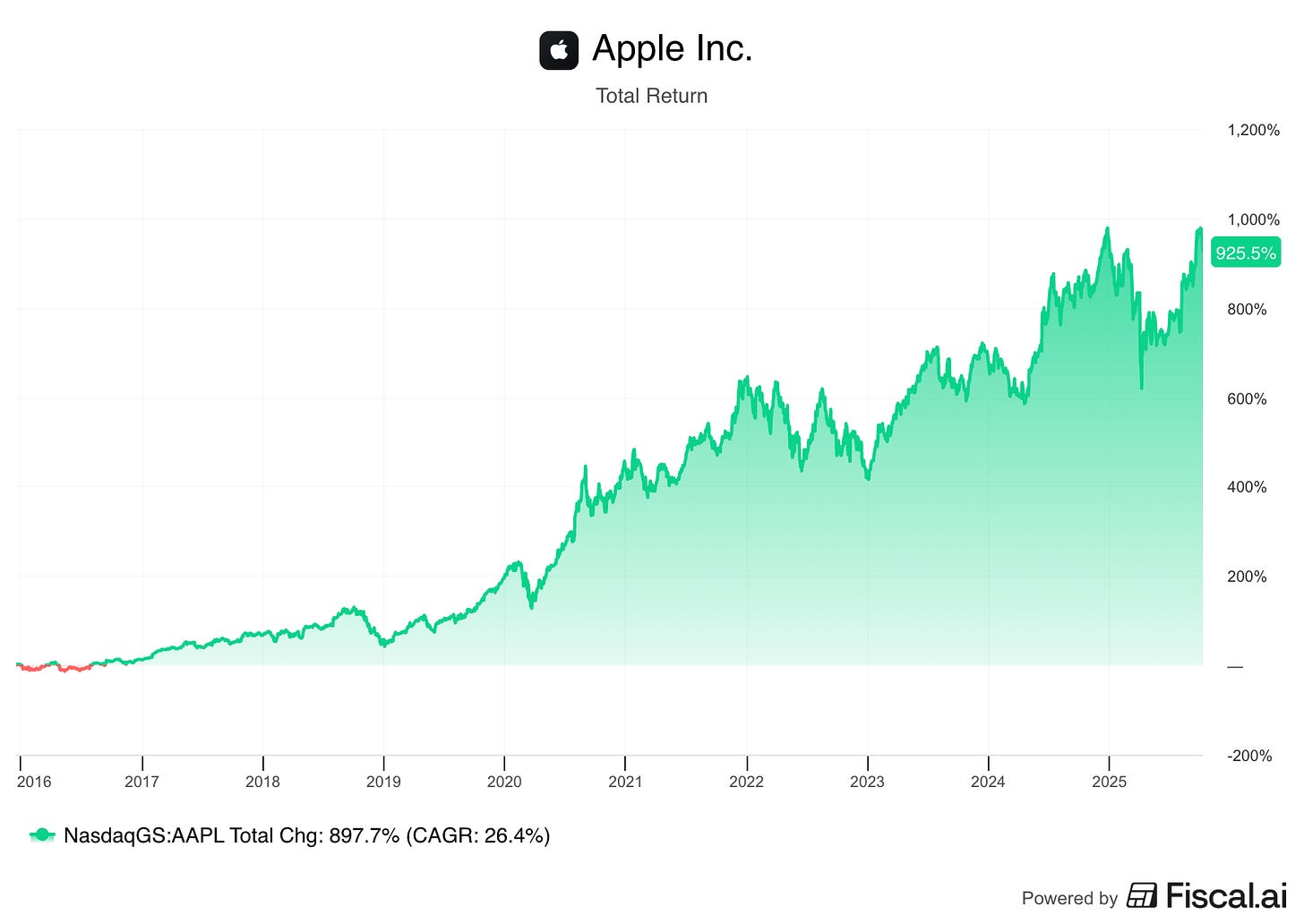

He bought Apple after all! Let’s look at that purchase.

Apple

Buffett bought Apple in the first half of 2016. It was around $25 a share during that time.

2015 EPS: $2.31

That’s about 11x earnings. Not exactly expensive.

Let’s look at another recent purchase:

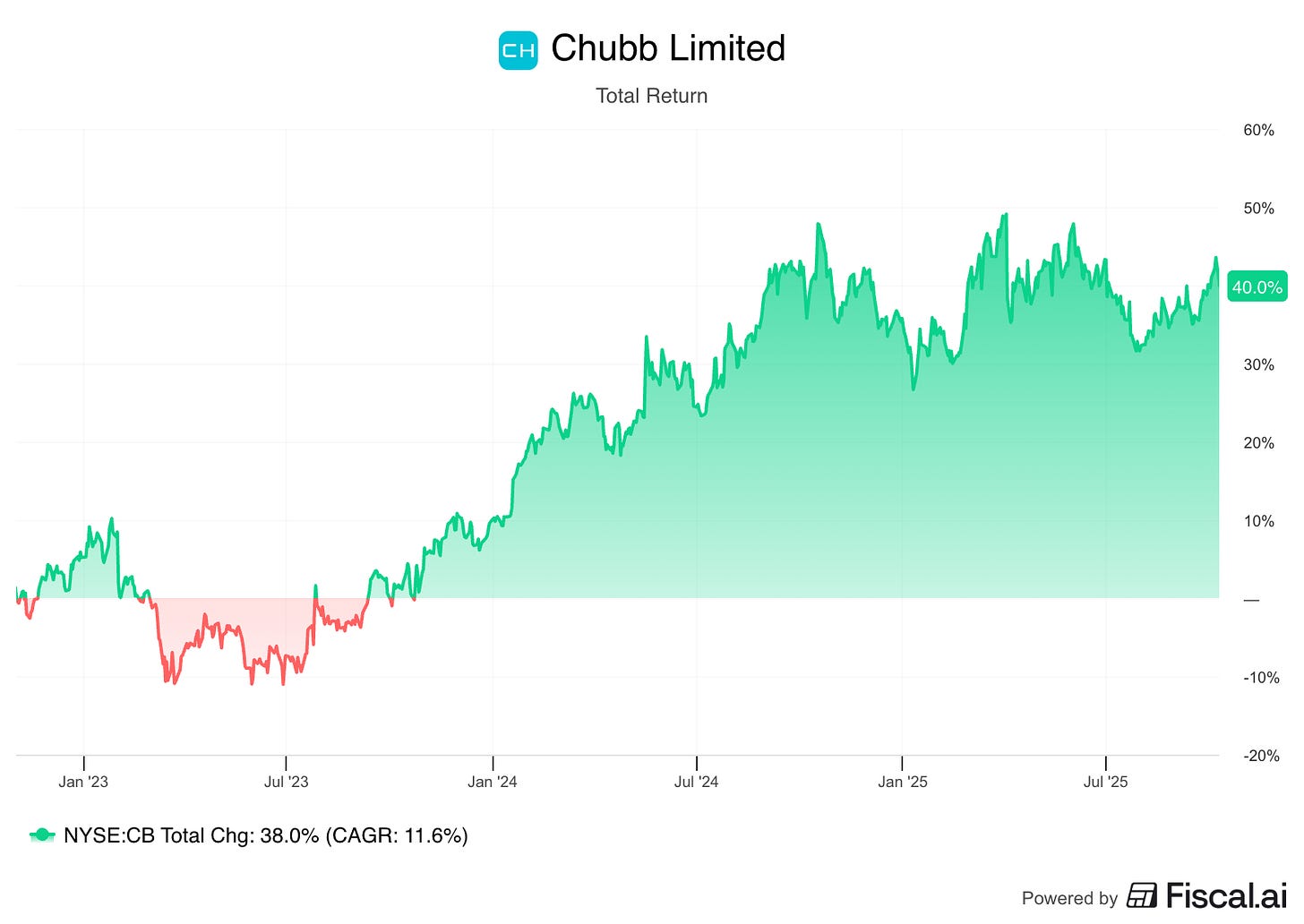

Chubb Limited

He initially started accumulating at the end of 2023, at $210 to $225.

2022 EPS: $12.40

PE: 16.9 to 18.2

Then he bought more in 2024, at around $260

2023 EPS: $21.80

P/E: 11.9

UnitedHealth Group

The most recent Berkshire purchase. Surely Buffett paid a lot - the Shiller PE is high, the Wilshire/GDP ratio is off the charts!

He reportedly paid about $312 a share.

TTM EPS: $23.10

P/E: 13.5

What’s NOT a Fair Price?

Even though Buffett moved from ‘value’ to ‘quality’ investing, he almost never pays more than 15× earnings, even for amazing companies.

He’s definitely not paying 30× or 40× earnings like many investors do today.

Why? I’ll show you.

The next few examples are quite old, and the data gets a little funky due to splits and adjustments by different data providers. So, for EPS and share prices, I went back to the actual 10-K documents from the companies.

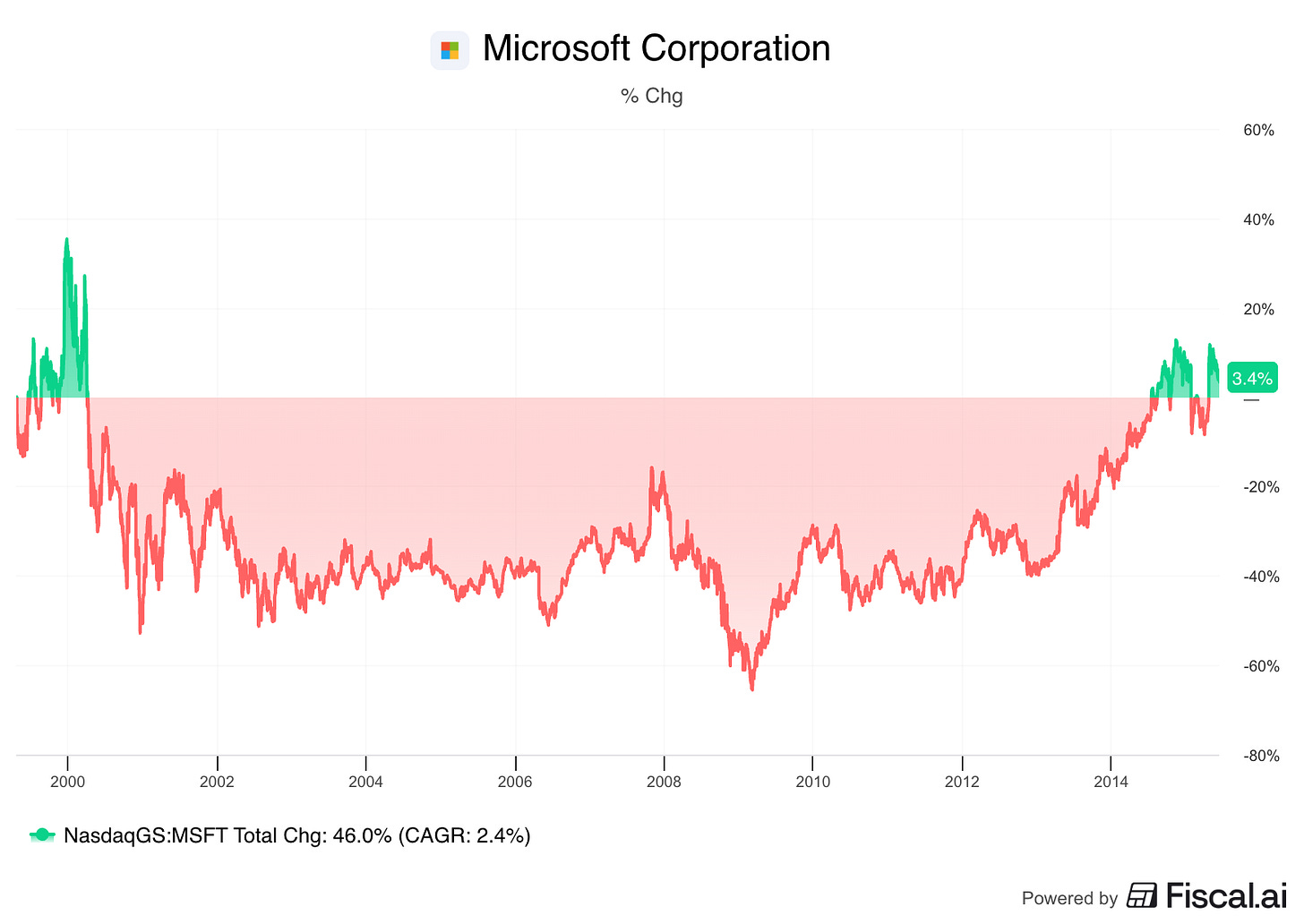

Microsoft in 2000

Microsoft was excellent in the 1990s and 2000s. So good in fact, that the U.S. government sued it in 2001 for being a monopoly.

But how did the stock perform?

EPS in 2000: $1.70

Stock price: $60.38 to $119.94

P/E ratio: 35–70.5

If you bought near the peak in 1999–2000, it took until 2016 just to break even.

Most investors probably didn’t hold that long.

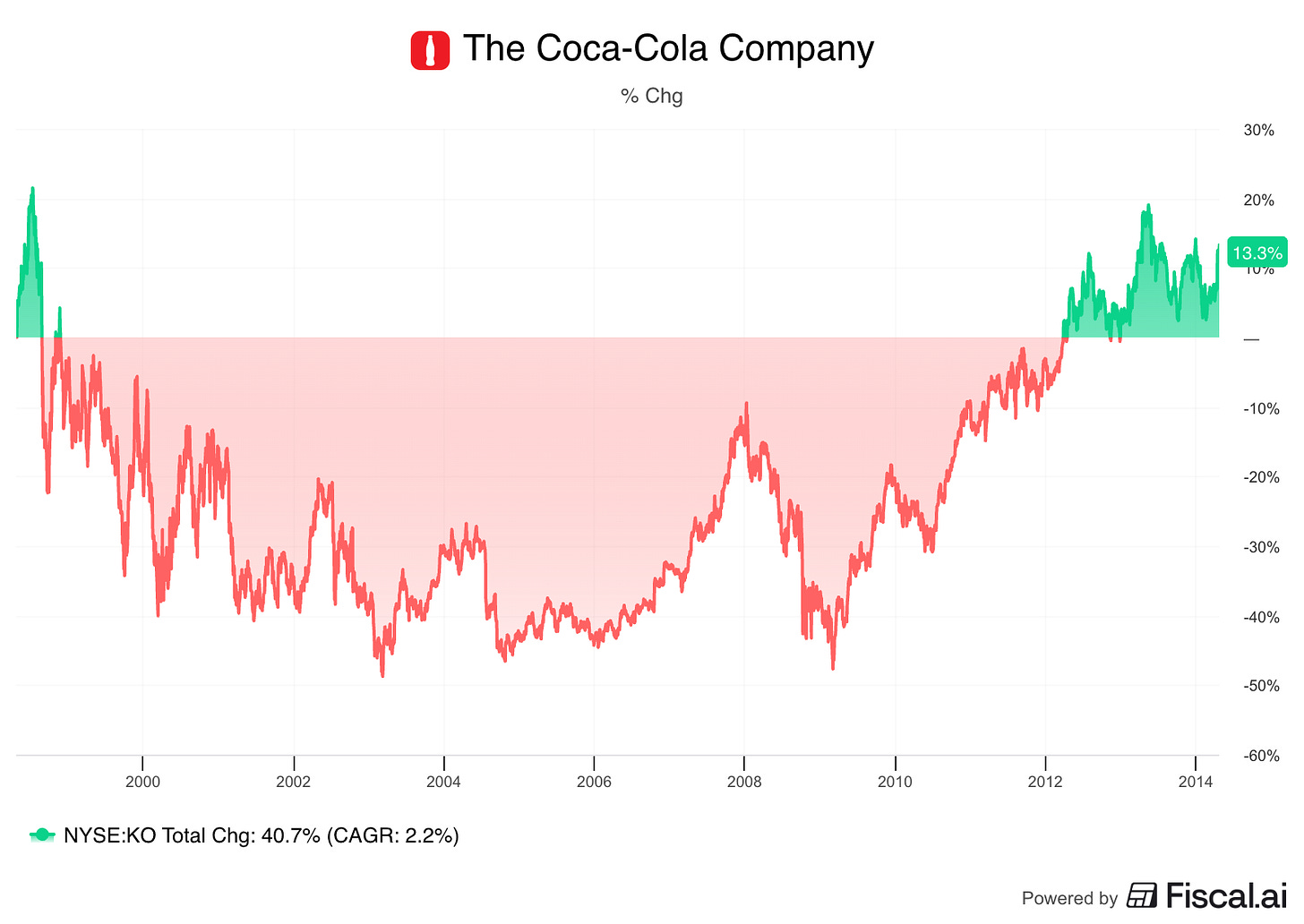

Coke

Here’s a Warren Buffett favorite! He’s said that he should have sold Coke in 1998, but didn’t because of the massive size of his holding and the tax

1997 EPS: $1.64

Closed 1997 at $66.69, Buffett said it traded around $80.

P/E ratio: 40.7× to 48.8×

If you bought in 1998, you briefly broke even in 2012 and had a short window in 2013 to sell for some gain. Again, if you held.

“It was always a wonderful business, but clearly at 50 times earnings, it was a silly price on the stock.”

That’s what Buffett said about Coke in the video above.

Both Microsoft and Coke grew their earnings during those years of flat stock prices.

But their P/E ratios fell so much that the stock prices went nowhere.

A great company is not always a great investment.

I think a lot of investors get so caught up in “compounding” that they forget what they’re trying to compound.

Paying too much for a business that compounds its earnings for years can still be a bad investment.

The goal isn’t just to find companies that grow earnings.

The goal is to grow our money.

Buying a good business at a fair price works. But it’s not the only strategy.

Buying undervalued businesses can work too.

You can earn strong returns through buybacks, dividends, and debt reduction.

And if you can get all 3... well that’s where the real magic happens.

On Saturday, I’ll share a company that I believe has all three.

It has the highest dividend yield in more than 10 years.

Its P/E ratio is also near a decade low.

And it has a strong track record of growth, supported by long-term trends.

Opportunities like this don’t show up often.

Paid partners will get the full breakdown.

Join us here so you don’t miss it. 👇

Test out Compounding Dividends risk free for 90 days here

One Dividend At A Time

-TJ

Used sources

Interactive Brokers: Portfolio data and executing all transactions

Fiscal.ai: Financial data

Disclaimer

As a reader of Compounding Dividends, you agree with our disclaimer. You can read the full disclaimer here.