💸 8 Rules of Dividend Investing

Every Wednesday it’s Dividend Day.

In this series, I will teach you 5 things about dividend investing in less than 5 minutes.

⭐ Big announcement ⭐

Next Saturday (12 October), we have a big announcement to make.

Starting then, Compounding Dividends will evolve into a full investment platform.

Stay tuned and make sure you don’t miss out.

1️⃣ Dividend payers are assets

Dividend-paying companies are valuable because they provide you with regular income.

They also tend to be stable and can continue growing, making them great long-term investments.

2️⃣ Dividends offer security and growth

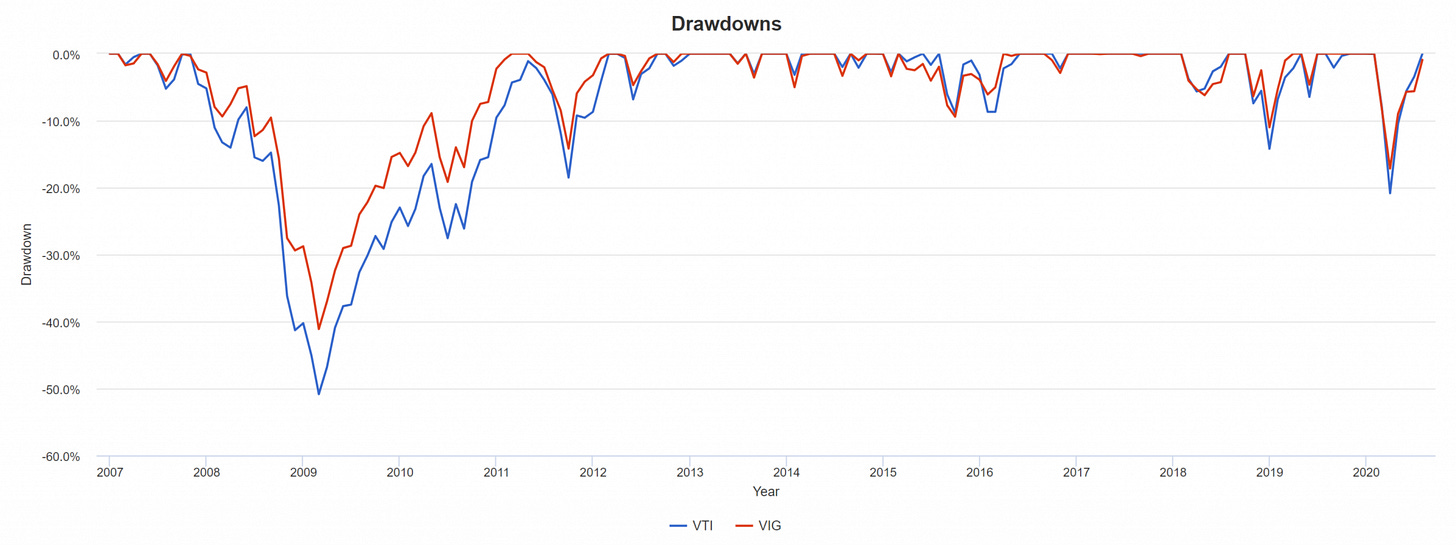

From January 2008 to the market bottom in 2009, the S&P 500 dropped by over 50%.

Dividend growers fell by less than 40%.

No matter what happens to the stock price, you will keep receiving your dividends if you invest in healthy dividend growth companies.

3️⃣ A dividend quote

Mark Cuban is a billionaire and the owner of the Dallas Mavericks.

He's also on the TV show Shark Tank where he invests in small businesses.

“I believe non-dividend stocks aren’t much more than baseball cards. They are worth what you can convince someone to pay for it.” - Mark Cuban

4️⃣ 8 Rules of Dividend Investing

Ben Reynolds wrote a paper on his 8 rules for dividend investing.

Here's a quick summary:

Choose stable, profitable companies.

Aim for a mix of high yield and dividend growth.

Look for sustainable payout ratios.

Sell if the stock gets too expensive or the business weakens.

Diversify, but not too much.

The image shows that 12 to 18 stocks provide most of the benefits of diversification.

Click on the picture to access the full PDF.

On Saturday, I’ll share my Dividend Investing Philosophy with you.

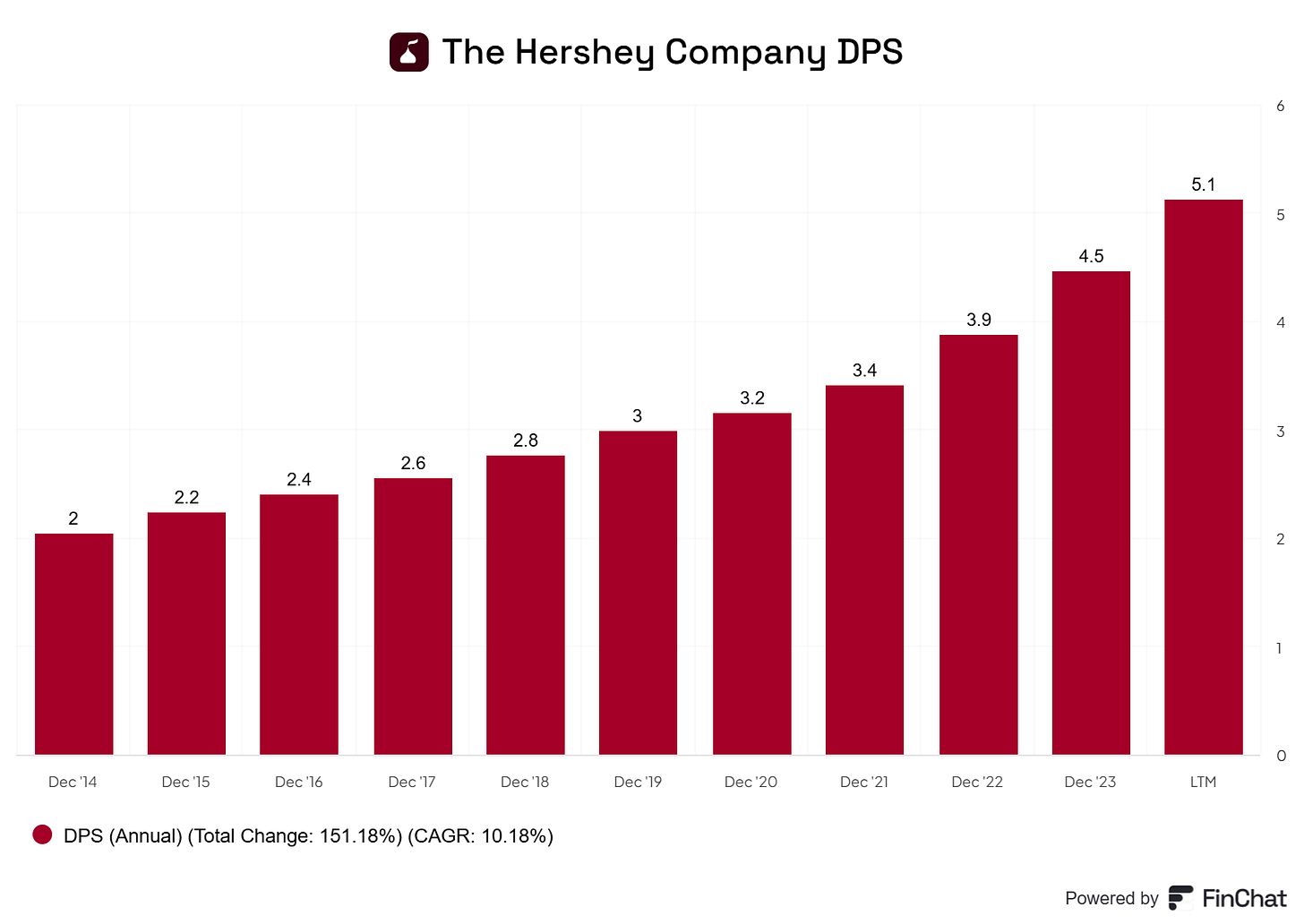

5️⃣ Example of a dividend stock

The Hershey Company was founded in 1894 (!).

They make money by selling chocolate and candy, including brands like Hershey's, Jolly Rancher, Cadbury, Twizzlers, and Reese's.

Profit Margin: 22.7%

Forward PE: 21.3x

Dividend Yield: 2.7%

Payout Ratio: 56.6%

Source: Finchat

That’s it for today

Stay tuned for our announcement next Saturday!

In case you missed it:

Used sources

Interactive Brokers: Portfolio data and executing all transactions

Finchat: Financial data

I'm not sure I would fully agree with Mark Cuban. What was the full context of his quote? Taken to some extreme, everything is worth only what you can convince someone to pay for it. Nothing would have any intrinsic value. We could be talking about cars, shoes, soda pop, or stocks. Look at Berkshire Hathaway and all the cash it has and all the cash it produces. Seeking Alpha says the P/B ratio is 1.64. What would the extra 0.64 be? You're also buying the management and the security and growth they provide through prudent capital allocation. Plus, you get admission to Berkshire's annual meeting. 🥰 That's got to be worth something too, right? 😉

The "Sure Dividend" article by Ben Reynolds provides a pretty good framework. It's easy to understand and easy to follow. 👍 I'm saving it into my collection of "Compounding" articles. I would tweak some of the rules. 👀

Rule #1. I'm OK with shortening the historical window from 25 years to 15 - 17 years. That window of time will take us back to the GFC. Going back further is looking at social and economic conditions that may not be as relevant. People's habits and the technology they use to scratch those habits have changed. Business operation and management practices have changed significantly. I understand the point being to see how the company behaved and operated under different economic conditions but I'm not sure we can necessarily apply all the lessons from 1999 in 2024 as we could have applied them in 2007. Otherwise, why stop at 1999? Some companies, like Coca-Cola, could be examined back even further! 💪

Rule #6. Rather than give a hard limit to the P/E ratio I would say look for a rate of change, especially after it exceeds a hurdle like +10% over historical averages. If the P/E starts growing high, quickly then question the business holding. 📈

Rule #8. The point of this is to diversify but what kind of diversification would you have if your 12 to 18 stocks are of businesses in the same sector or industry? You could be building up some kind of common systemic risk. In this case, I think it would be OK to be a little bit of a "stock collector" and own businesses that do not fully relate to each other. Have 2 or 3 financials, 2 or 3 industrials, 2 or 3 consumer staples, 2 or 3 REITs, etc. And it's OK to have the common stock and the preferred stock counted together as 1 holding. This rule can bring up a lot of good conversations about portfolio management and sizing. Do you own enough of each business so the dividend payment is the same from each company? Do you put more into companies with lower valuations despite a lower dividend payout? I don't think there is a right or wrong answer. It's a matter of what do you want more along the way.

Each rule by itself, if taken to an extreme, can be risky. Using all the rules together to balance each other out will be harmonious. 😊